Despite being Nepal’s capital city and the administrative and political hub, Kathmandu Valley continues to reel under an acute drinking water crisis. The irony is striking—while the city symbolizes national progress, its residents’ queue for water jars, dig deeper wells that run dry, and pay exorbitant fees to private water vendors. Even in my own household, we grapple with dry taps, an empty well, and an erratic Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited (KUKL) supply. To manage daily needs, we’ve had to install an underground tank, rooftop reservoir, water pumps, and filtration units. Each of these incurs financial, physical, and mental burdens—particularly on women, who bear the responsibility for water management in most homes.

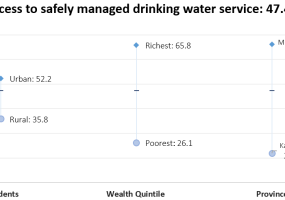

This is not just a personal story. It reflects the collective struggle of Kathmandu’s population and, indeed, much of Nepal. According to the Ministry of Water Supply’s Joint Sector Review 2023, only 19% of Nepalis have access to safely managed drinking water. While 57% have piped connections, 9.9% have limited access, and 13.3% remain entirely unserved. Even with a legacy of water systems dating back to 1891—like the historic Bir Dhara—progress remains slow, and the gap between infrastructure and reliable service has only widened.

Kathmandu Valley currently demands around 506 million liters of water per day, yet KUKL is able to supply average only 240 million liters—less than half the required amount. The deficit is filled through expensive private water tankers, household-level groundwater extraction, and self-supply systems that are often unsafe and unsustainable. These “solutions” place an inequitable burden on low-income families, who must either spend a disproportionate share of their income or settle for compromised water quality.

It has been nine years since Nepal’s constitution declared water and sanitation a fundamental right. Yet, that right remains elusive for millions. Legal frameworks such as the Water and Sanitation Act 2079, the WASH Policy 2080, National drinking water quality standard 2079, water and sanitation guideline 2081, and the recent water and sanitation tariff guideline have laid a foundation for reform. Point 97 of this year Plan and Programme even reiterates Nepal’s commitment to ensure quality water access for all citizens. But policies alone don’t deliver water—effective governance, capable service providers, and sufficient investment do.

Unfortunately, the sector’s budget has shrunk, and budget utilization remains poor. Weak coordination among federal, provincial, and local governments hinders implementation. Meanwhile, the water sector lags in adopting new technologies, improving asset management, and institutionalizing quality monitoring. Despite multiple actors—KUKL, Nepal Water Supply Corporation (NWSC), Water and Sanitation Users’ Committees (WSUCs), private vendors, and individuals—the service delivery landscape remains fragmented and inconsistent.

Even well-established providers like KUKL and NWSC are unable to meet demand or maintain consistent quality. In rural and remote areas, WSUCs operate mostly on a voluntary basis, with unclear roles, weak accountability, and little support from local governments. While these committees played a crucial role in expanding access in previous decades, the WSUC model needs to be re-evaluated to address the demands of a growing urban population, escalating climate risks, and increasingly complex water needs.

Water scarcity in Kathmandu is not just a public service failure—it’s a daily crisis for families, especially women. Households must invest heavily in coping mechanisms: filtration units, tankers, jars, extra plumbing, and water testing. These recurring costs are not reflected in official service statistics but weigh heavily on household budgets. Water that should be a basic right has turned into a luxury commodity, more easily accessible to the well-off. All the burden and additional costs required to secure drinking water could be eliminated if each household had a 24/7 supply.

Women, in particular, shoulder the invisible labor of water scarcity—planning usage, collecting water, filtering, storing, and rationing. This unpaid burden impacts their time, health, education, and mental well-being. When basic water needs are unmet, it undermines human development outcomes: girls miss school, hygiene deteriorates, and families are exposed to disease.

The fragmented, informal, and outdated service delivery system cannot solve Nepal’s water crisis. What the country needs is a unified, professional, and accountable model for water service delivery. Lessons can be drawn from sectors like health, electricity and education, which maintain structured institutions with trained personnel—even in rural regions. Water, being just as essential, deserves the same level of institutional commitment and capacity.

Globally, over 475 Water Operators’ Partnerships (WOPs), involving 758 utilities, are active under the UN-led GWOPA initiative. These non-profit peer collaborations strengthen utility performance through mentoring and technical support. Many countries now promote national-level WOPs to professionalize services and scale up knowledge exchange.

Nepal urgently needs to establish a National Water Operator Partnership (NWOP) uniting KUKL, NWSC, WSUCs, and private providers. With over 42,000 WSUC members nationwide, this platform can drive collective transformation through structured training, peer mentoring, and certification. NWOP can identify service gaps, support reforms, promote digitalization, strengthen water quality monitoring, and standardize tariffs. It can also boost employment, advance climate-resilient infrastructure, Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM), and inclusive services, and uphold the constitutional right to water, asset management, and digitalization.

After the government invests in water supply schemes and hands them over to service providers, it is expected that providers collect tariffs and manage regular operation and maintenance. However, this is not happening in many parts of Nepal due to weak institutional structures, limited technical staff, low willingness to pay, and public misconceptions. The Nepal Water Operator Partnership (NWOP) can play a key role in improving system performance and supporting scientific tariff setting and collection. Experts suggest an average monthly tariff of NPR 250 per household and an annual NPR 600 per person could ensure sustainable service. With 57% of households already connected to piped systems, proper management could generate over NPR 10 billion annually, supporting maintenance and job creation. As coverage expands, adopting a professional utility model through NWOP will be essential for sustainable and reliable water service delivery.

Nepal stands at a crossroads. Decades of investment in water infrastructure risk falling short without effective operation—like pipelines without water. It’s time to move beyond fragmented efforts toward integrated service delivery, professional management, and equitable access. Institutional capacity, not just infrastructure, will determine whether every Nepali access safely managed water. A National Water Operator Partnership offers a globally recognized solution to build that capacity. With clear vision, coordination, and government backing, NWOP can protect public investment and ensure reliable, inclusive water services for all.

(Mr. Gautam is a WASH sector professional. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official position of any affiliated organization. Anand Gautam | LinkedIn)

1373 पटक हेरिएको

1373 पटक हेरिएको